Ilaria: What it made me think of just now was the performative act; there is a performance impact in using that fork and knife and in doing etiquette. When we enter an archive as a researcher and we get into that rabbit hole, we don't like to think about it but we put on gloves, we put stuff on a cushion, we approach the object in a - I don't want to use the term 'normative' but - we would have a different temporality in approaching the object; there will be a different temporality for a person with two hands eating. This temporal question is so entangled with the archive itself. Should we let it go back to its original state of dust or should we conserve it? It's all a question of difference of temporalities and how we play with them.

And it's also the digital you know.

Ilaria: What it made me think of just now was the performative act; there is a performance impact in using that fork and knife and in doing etiquette. When we enter an archive as a researcher and we get into that rabbit hole, we don't like to think about it but we put on gloves, we put stuff on a cushion, we approach the object in a - I don't want to use the term 'normative' but - we would have a different temporality in approaching the object; there will be a different temporality for a person with two hands eating. This temporal question is so entangled with the archive itself. Should we let it go back to its original state of dust or should we conserve it? It's all a question of difference of temporalities and how we play with them.

And it's also the digital you know.

Clink

Clink

Clink

Clink

reality

Imagined v real?

You imagine the feel of the cold metal prongs pressed against your tongue. You push your finger into your mouth and feel the fresh incision.

You’re bleeding. The blade has sliced into your tongue.

But how can an object that you do not have, cut a tongue that it has not touched?

gather round the object,

there is no leader

You imagine the Nelson pattern. You see it right in the middle of your mind’s eye. You know it well. You have seen it so many times on your laptop screen.

A cold metal fork with three prongs. The fourth prong is a small and blunt serrated blade affixed on the side. An opalescent burnished patina clings to the surface of the combined knife and fork, bruised by time.

You can almost hear a blade scraping against a china plate. A screeching sound that feels internal. The noise cuts through you and you begin to taste metal.

But is the object the leader?

Is the object's voice the sound that we are listening to?

Must we tune into object listening to sit at the table?

What does the object's voice sound like?

What is it saying?

Who has the right to speak back?

It presents a fictionalised reality of the object (Nelson pattern, a combined knife and fork), which by its very nature in the digital archive is unstable and contingent, quivering between being absent and present. This provocation highlights both the instability of the archival object and the role of language in re-contextualising, reimagining and redefining the experience of an object reality.

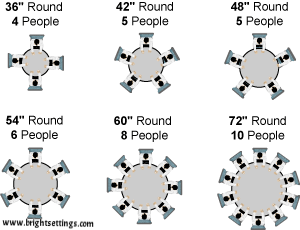

"Research has revealed that the more often people eat with others the more likely they are to feel happy and satisfied with their lives."

Oxford University

and give it imaginary vitality

connect with

objects and

with others?

experience

isn't always

a bad thing

Experience

with the object/with others?

Are we only touching with hands?

Do we touch with our gaze?

Is touch giving agency?

Is touch caring or harmful?

Can the same touch be both?

Are they afraid of your touch?

Or the touch of

the object?

And who the hell

are ‘they’ ?

Serendipity as methodology

Jacky: And that lends itself to certain disciplines more so than others. When we picked the object I was hoping that we might end up with a video with sound, and then we ended up with an image and I was like 'and I'm doing sound'. But we discussed a lot from an artistic perspective and the music perspective, like challenging the archive: is it described by timbre, by colour. There are barriers to us describing those pieces from a visual arts and sonic perspective because the descriptors don't allow for that, they allow us to search by age (for example) and there's a bias in-built within a much bigger archive system that exist formany reasons like record keeping, but it's a challenge when you're working outside of language or outside of history.

Ownership;

personalisation;

identity -

Imperial War museum Britsh Army fork:

History note

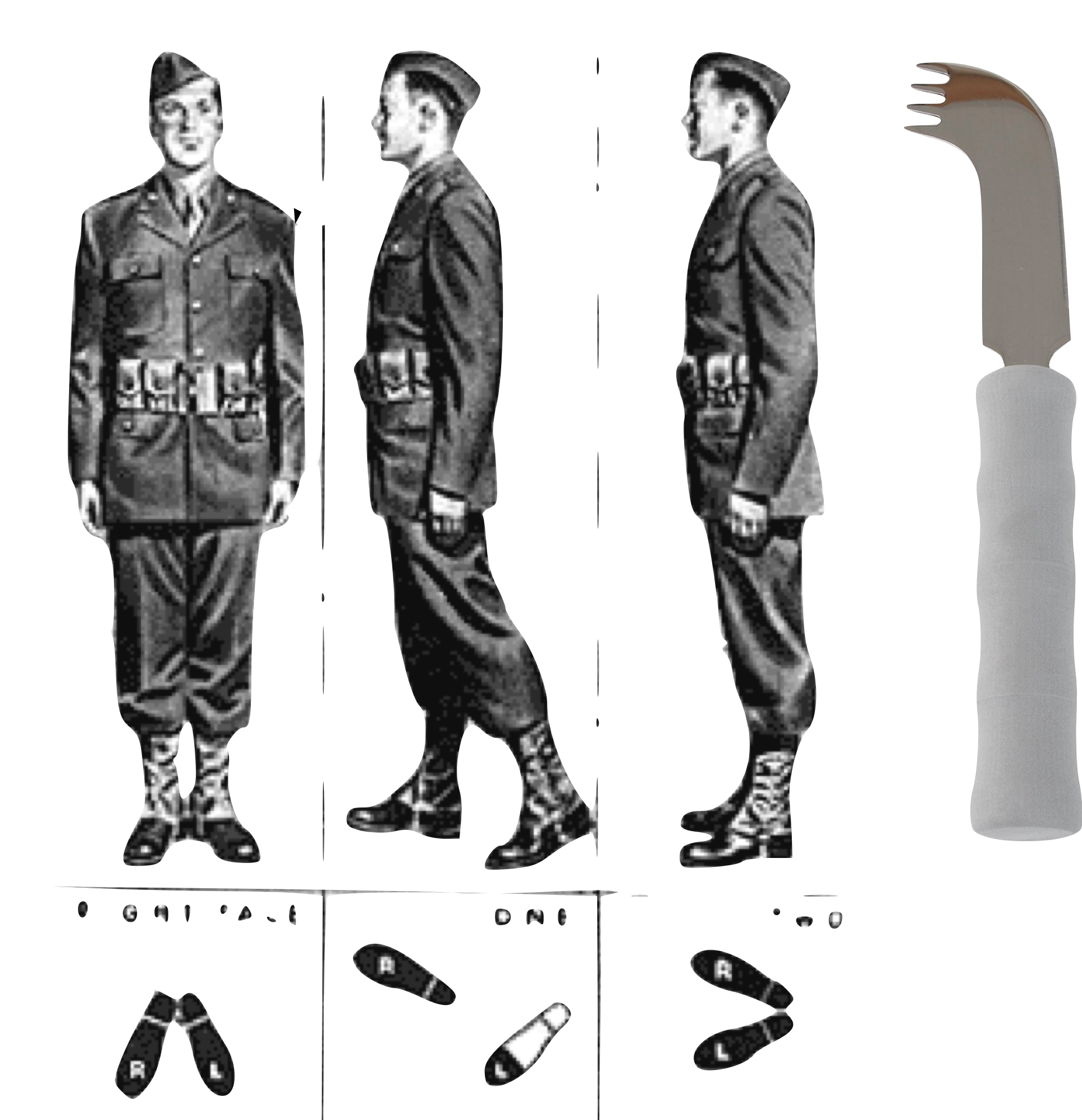

A basic pattern of knife fork and spoon cutlery (collectively known as 'KFS') were issued to all soldiers, with some units adopting the practice of stamping the man's last three digits of his personal service number to the handles. During the Second World War a clip-together set were issued, and this very practical arrangement continues to be issued today

Turn from the cut

concentrate on wellbeing.

What can health mean when rehabilitation, nurturing and nutrition are all delivered on a knife edge? To feed yourself is to consume the cut with every mouthful. Is it any wonder there are little words on record of this experience, if the lips and tongues were preoccupied with negotiating the danger.

Silenced by the

conditions of the museum

“sound objects, unlike visual objects, exist in duration, not in space: their physical medium is essentially an energetic event occurring in time” Schaeffer, Pierre (2017). Treatise on Musical Objects: Essays Across Disciplines (trans. Christine North and John Dack).

Oakland: University of California Press.p. 190.

Marcel Duchamp's 'With hidden noise' (1916)

Duchamp explained in a 1956 interview,"Before I finished it Arensberg put something inside the ball of twine, and never told me what it was, and I didn't want to know. It was a sort of secret between us, and it makes noise, so we called this a Ready-made with a hidden noise. Listen to it. I don't know; I will never know whether it is a diamond or a coin" (Sanouillet & Peterson 135).

A Lovers' Telephone

You will need:

2 paper cups

8 metres of string (approx.)

1 pencil

How to:

1. Make a hole in each cup using the point of a pencil

2. Thread the end of the string through one hole into the cup

3. Tie the end of the string inside of the cup into a tight knot

4. Repeat this with the second cup

5. Each person holds a cup, making sure the string is taught, taking in turns listening and speaking

'A 19th century tin can, or lovers' telephone' (1889) Ebenezer Cobham Brewer and François-Napoléon-Marie Moigno, Hvarför? och Huru? Nyckel till naturvetenskaperna, 1890. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

'Sound is ubiquitous, unstoppable, immersive, the agency through which spoken language is understood and music is absorbed. Sound works quietly with other senses to scan an environment, to define orientation within a place, to register the feeling that we describe as atmosphere. Without sound, the world can be an indecipherable, remote and dangerous place, yet sound is the sense that we take for granted'

whiteness

white noise

white washing

What if nothing feels the same what can be built in a world not built for you

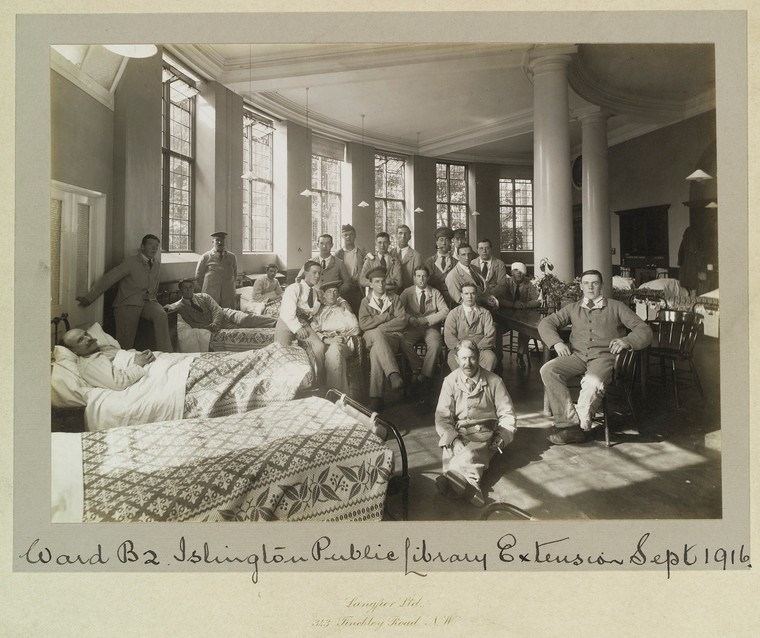

With careful hands and pain in their eyes, they gather around their comrade, their friend, perhaps their lover. His arm is no longer there - he looks to the absence of himself. His jacket ripped now pleats around his wound. There is a stillness and silence here as tenderness lingers on the skin.

What then is left if there is no other hand pain?

pure sound?

on the other hand

on the other hand

on the other hand

in the other hand

the other

other

an empty sleeve?

Eating a meal using only one hand can be difficult. The design of this combined knife and fork is known as a Nelson pattern, named after Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), the British naval hero who lost an arm during the Battle of the Nile in 1798. He was presented with a similar knife made from gold. This silver plated knife dates from the First World War. Many of the thousands of arm amputees from that conflict were issued with these Nelson knives as part of their rehabilitation. A simple, but highly effective design, Nelson knives are still available today. This example was previously owned by the Royal United Services Institute. They were established in 1831 and continue to research and study every aspect of national defence and security, including military tactics and terrorism, maker: Unknown maker Place made: Europe

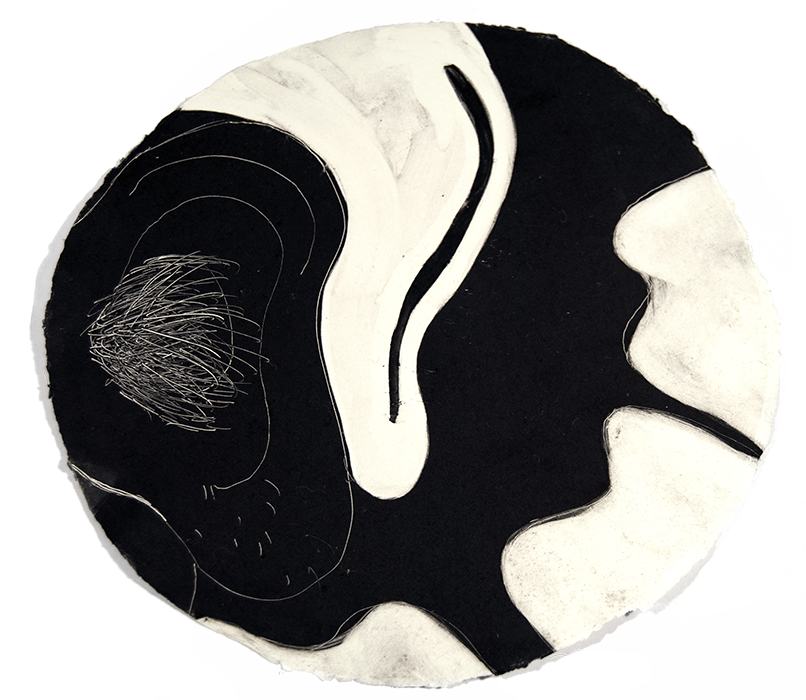

Robert Smithson formed a new model of time, which he called 'crystalline time'. The crystalline screw's dislocation acting as a metaphor for time, “spirals that reverberate up and down space and time.”

The Collected Writings. ed. by Jack D. Flam (London: University of California Press, 1996) , p.56

Lost in space

Lost in this space

Lost in time

Lost to time

What disappears in the process of documenting others?

"The future criss-crosses the past in an unobtainable present."-

Robert Smithson, “Quasi-Infinities and the Waning of Space”, The Collected Writings. ed. by Jack D. Flam (London: University of California Press, 1996) , p.34

Kat: "In our example, it seems that a conventional fork has been modified with a blade replacing one of the prongs or tines and kept in place with a screw. I’m struck by the ordinariness and the familiarity of this object – the fork and its handle take a very recognisable form – a combination of the Old English and Fiddle patterns of cutlery dating from the mid-eighteenth century that would have been recognisable to viewers/users both then and now..."

The recognisable form of the combined knife and fork is interesting because we, the viewer, become temporally suspended - trapped between our own time and the object's. How do we make sense of the temporal dislocation that the archival space creates.

Fiona: I like the idea of asking ‘what does this object want?’ If you had to respond to this question, what does any archival object want?

Things? Objects? Artefacts?...

When does a thing become an object (or vice versa?)

Are objects related to function? When it is picked up and used? Does focused attention make a thing into an object? Is our combined fork an object or a thing (why do I use 'ours' here? I don't like the ownership this implies so why did I use the possessive here? weird.) Function seems important here for the combined knife and fork - the function of the object changes - a fork becomes a fork and knife.

The Archival Imaginarium was originally presented at the Northern Network for Medical Humanities Research Congress. University of Sheffield, 23-24 January 2020.

Taking Wellcome’s digital Collection as its starting point, we asked how the digital encounter influenced the way medical humanities research is conducted. Researchers frequently describe experiences of a collection through notions of chance, in ‘happening upon’ or ‘discovering’ items. However, the organisational framework placed on the material is masked through catalogues, hierarchies and search terms. This invisible framework limits and governs the stories told by implicitly shaping the responses that researchers then formulate.

Brian Eno’s (1975) ‘Oblique Strategies’ were used as a serendipitous model for engaging with Wellcome’s digital Collection and ask how we might reimagine the archival experience with chanceas our guide. By displacing the organisational framework, there is thepotential to expose choices, exclusions, and gaps that are inevitable, butoften invisible, in any collection.

Four ECRs each created a response to the same object, ‘Combined knife and fork’ (1914-1918), chosen at random using an Oblique Strategy as a non-hierarchical digital collection search tool. Each provocation uses an Oblique Strategy as title and prompt, and draws upon the participant’s particular disciplinary expertise. This highlighted the diversity of potential modes of experiencing and understanding the archival medical object, and suggesting ways in which these multiple modalities of approach might shape original perspectives on health and its associated concepts.

The Archival Imaginarium returned to the digital through a process of asynchronous auto-archival-dreaming. It offers opportunities to resist or participate in becoming archived, and if it is possible to tell the difference.

Olivia Turner - What is the reality of the situation?

Bentley Crudgington - Do the words need changing?

Dr Jacqueline Waldock - Convert a melodic element into a rhythmic element’

Katherine Rawling - Do the washing up.

The Archival Imaginarium emerged from the Thinking Through Things project and was funded by a Wellcome Trust Discretionary Award.

Web development and animation by Adrian Everett.